It had long been argued that, in spite of what hockey fans claim, lacrosse is Canada’s national game.

Lacrosse has certainly been played in Canada longer than hockey. Indigenous peoples were playing lacrosse (which they called baggataway and tewaarathon) when Europeans first arrived in what is now Canada.

A game back then might involve hundreds of players and could be so rough, it made hockey look like a stroll in the park. It wasn’t uncommon for players to be seriously injured or even killed.

The game has figured in our history in more ways than just being a spectator sport. During the conflict known to history as Pontiac’s War (1763 – 1766), a ball tossed through the open gate of a frontier British fort during a lacrosse game was the signal for warriors to attack. The solution to the Canadian lacrosse/hockey debate wasn’t quite as dramatic.

In 1994, parliament passed Bill C-122, which recognized lacrosse as Canada’s official summer game, and hockey as the official winter game.

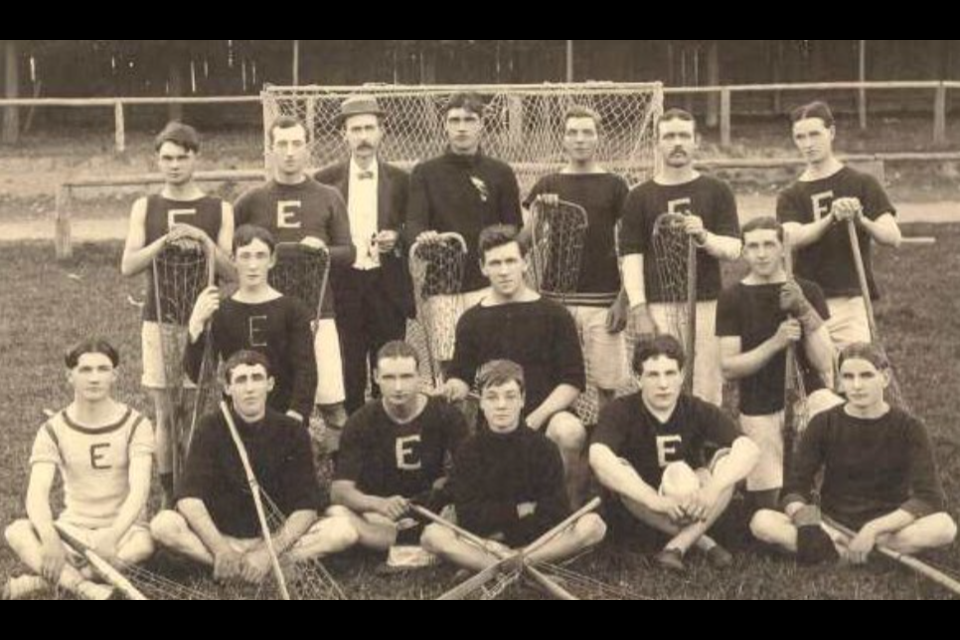

The friendly rivalry between neighbours Elora and Fergus has involved many aspects of their shared history and development, sports not being the least of them. Lacrosse has been part of that rivalry, with both towns fielding outstanding teams.

Both Elora and Fergus have had lacrosse teams since the mid-19th century. It quickly surpassed games like cricket and even curling in popularity. The communities have been represented by teams of various names (the Elora Mohawks, for example), but the best known have been the Elora Rocks and the Fergus Thistles, two of the oldest lacrosse clubs in Canada.

In the early days the clubs had no real coaches or managers. They were organized for just one season, which usually lasted from May until September. Games on public holidays were especially popular. There were no periods or time limits. The first team to score three goals won.

Sometimes it could take a very long time for someone to get that third goal. Eventually, periods and time limits were instituted.

Initially, lacrosse games were always played outdoors. Later, matches were held indoors in arenas. This was called “box” lacrosse.

Most of the players were in their 20s and 30s and came from merchant households. Working class men usually couldn’t afford to take time off the job to be involved in lacrosse. There were also expenses.

Team members shared costs, including for travel and accommodation when games were out of town. Admission was charged to games, and gate receipts were divided between the teams and then distributed to the players.

An important, much-anticipated match could draw a big crowd. But sometimes the spectator stands were almost empty.

Originally there was no rule book, and the games played in Fergus and Elora could resemble the melees that took place in the old days when the Indigenous teams battled with no holds barred. The players wore no protective equipment.

A book of lacrosse rules appeared sometime in the 1860s, but a long time passed before it was universally accepted. Even then, sometimes things could get out of hand, especially if overenthusiastic fans got involved.

The Toronto Globe reported on a game that took place in Guelph on Sept. 28, 1907. It wasn’t an Elora vs Fergus match, but incidents of the kind were not uncommon.

“In a drenching rain, piercing wind and with thunder and lightning alternating with fistic disturbances in providing additional excitement, the Rocks of Elora proved conclusively their right to the intermediate C.L.A. (Canadian Lacrosse Association) championship by defeating the Maitlands of Toronto by 8 goals to 3. The game was played on the Exhibition grounds here this afternoon before a crowd of perhaps five hundred shivering enthusiasts, nearly all of whom came by special trains from Elora and Toronto.

"All went as well as the state of the grounds and the atmosphere would permit until toward the end of the third quarter, in which a fight at the Elora goal took place, where a Maitland home player was apparently the first offender and struck the first blow. The fight developed into a free-for-all, the players and crowd getting entirely beyond the control of referee (Fred C.) Waghorne and the police on the grounds.

"A few minutes later, all had retired from the grounds but the players and a few Maitland supporters who banded themselves together in the centre of the field and refused to leave … additional police were sent for … the grounds were cleared and the game proceeded with.”

That game was considered one of the most memorable in Elora lacrosse history.

The era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the golden age for lacrosse in Elora and Fergus. After that, the game’s popularity and the two communities’ level of success saw peaks and valleys.

Teams from Elora won championships in 1903, 1907, 1967, 1968, 1976, 1999, 2005 and 2018.

The Fergus Thistles won championships in 1931, 1960, 1965, 1966, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1990 and 1992.

One of the star lacrosse players of the 19th century was Elora goaltender Sam Stephenson, a watchmaker by profession. His combination of sheer size and exceptional agility made him seem like a wall in front of his team’s net.

Since Stephenson’s day, many people representing Fergus and Elora clubs’ players, management and team builders have been inducted into the Canadian and Ontario Lacrosse Halls of Fame; among them: Bob Hamley, Ron “Putsy” Landoni, Pat “Wheels” Mackenzie, Annie McDonald, Joe Bergin and George “Hec” Mackenzie.

One noteworthy Fergus player was Wilfrid Kennedy “Bucko” McDonald (1911 – 1991) who also had an outstanding career as a defenceman in the NHL. The Ontario Lacrosse Association’s Bucko McDonald Trophy, named in his honour, is awarded to the league’s highest-scoring player.

Hockey and lacrosse! As a Canadian, Bucko apparently had the best of both worlds.