A 19th century hymn titled The Ninety and Nine, which was among the most popular sung in churches and at evangelical gatherings in the English-speaking world, and is still heard today, has a connection to Fergus.

The lyrics, at first glance, are a re-telling of the biblical parable about Jesus, the shepherd who leaves his flock of 99 sheep to go in search of one that is lost. Here are the first and last of the hymn’s five verses:

There were ninety and nine that safely lay

In the shelter of the fold;

But one was out on the hills away,

Far off from the gates of gold.

Away on the mountains wild and bare;

Away from the tender Shepherd’s care.

And all through the mountains, thunder-riv’n,

And up from the rocky steep,

There arose a glad cry to the gate of heav’n,

“Rejoice! I have found My sheep!”

And the angels echoed around the throne,

“Rejoice, for the Lord brings back His own!”

However, the hymn’s author, Elizabeth C. Clephane was moved by more than biblical inspiration, for the “lost sheep” she was writing about was her own brother, George, whose final resting place is in a Fergus graveyard.

George and Elizabeth Clephane were born to a fairly well-off family in Fifeshire, Scotland; George in 1819 and Elizabeth in 1830. Their father, Andrew Clephane, was the local sheriff.

Nothing is known of George’s early life, except that he sailed for Canada in 1842 aboard the immigrant ship Souter Johnny. He was coming to his new country as a remittance man, which meant he might not have left home entirely of his own free will.

A remittance man was a person from a respectable, financially well-to-do family who was something of a black sheep. A scandal or his generally bad behaviour had embarrassed his family to the extent they had told him he would be paid an allowance, called a remittance, if he would just get out of the United Kingdom. Many remittance men went to Canada or the United States. A few of them used the opportunity to start up a productive life in a new country, but many were wastrels and downright scoundrels, living off money from home while contributing nothing to any community in which they alighted.

George Clephane had a drinking problem, but it isn’t certain if that alone was the reason for his banishment from Fifeshire. On board the ship carrying him across the Atlantic he met a man named Thomas A. Young who was traveling to the newly founded village of Fergus. The pioneer community favoured Scottish settlers, so George evidently decided that was the place for him to go to and try to make the best of his exile.

Clephane settled in a little house or cabin on a small farm just north of Fergus on the east side of the Owen Sound Road. In a Guelph Mercury article published in 1927, journalist A.E. Byerly wrote of an interview he’d had with Mrs. James Skeoch, a nonagenarian who had known Clephane when she was a child. She said he was a gentleman who always showed great consideration for others. But he wasn’t cut out to be a farmer and so wasn’t very successful at it. He sometimes became despondent. There is documented evidence he made a request to have the amount of his remittance increased. Byerly also met the daughter of Thomas Young, who told him Clephane was fond of horses. She owned a riding whip that had once been his.

One problem Clephane encountered was the fact that in that frontier region, whisky was cheap and plentiful. When he would fall into a bout of depression, liquor was easily at hand and he would get drunk.

In 1851, Clephane was thrown from his horse and suffered serious head injuries. He was taken to the home of a friend, Dr. Mutch, where he died on May 2 at age 32. His funeral was held in St. Andrew’s Church with the service conducted by Rev. Dr. Mair, and he was buried in the churchyard cemetery.

News travelled slowly in those days, so many weeks passed before the sad tidings of George Clephane’s untimely death in Fergus reached Fifeshire. His sister Elizabeth was heartbroken. Byerly wrote in his article, “… she bent over her desk and from the throbbing ache of that bleeding heart penned the cry of an anguished soul.” That was her hymn, The Ninety and Nine.

Elizabeth wrote several other hymns besides The Ninety and Nine. Among them were Beneath the Cross of Jesus, Into His Summer Garden, From my Dwelling Midst the Dead and The Day is Drawing Nearly Done. None of her work was published in her lifetime. Her health was always frail, and she died in 1869 at the age of 38.

Between 1872 and 1874, eight of Elizabeth’s hymns were published in The Family Treasury, a Presbyterian magazine. The Ninety and Nine was by far the most popular. In 1874 an American composer named Ira Sankey put the words to music. He later included it in a best-selling collection called "Sacred Songs."

Sankey toured North America and the United Kingdom with a revivalist preacher named Dwight Moody. Their travelling religious show drew huge crowds and the singing of The Ninety and Nine was always a high point. Sankey would stand up at his organ and ask the crowd, “How many prodigal sons may be restored to their homes today?”

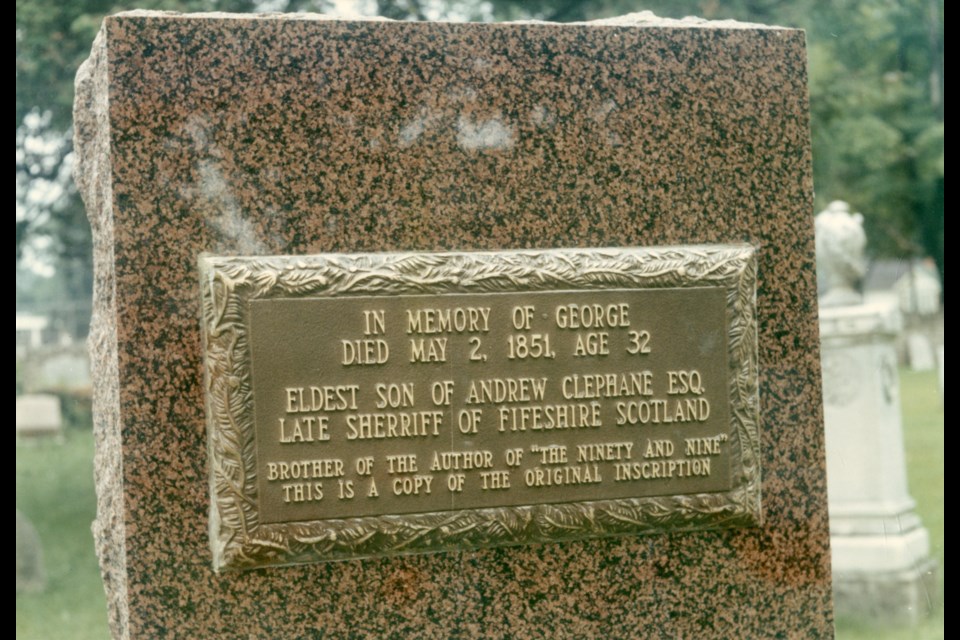

The grave of Elizabeth Clephane’s wayward brother can still be seen in St. Andrew’s Auld Presbyterian Kirkyard in Fergus, marking one of the community’s connections to literary fame. Its inscription reads, “In memory of George, died May 2, 1851, age 32. Eldest son of Andrew Clephane Esq. Late Sheriff of Fifeshire Scotland. Brother of the author of The Ninety and Nine.”