The Grand River is central to the largest drainage system in Southern Ontario. The history of human impact on the area should be a cautionary tale in this time when the fate of Ontario’s Greenbelt is in question.

Also worthy of a retelling is the story of the Fergus newspaperman who played a major part in that tale in the mid-20th century.

Unlike the Indigenous peoples who originally lived in the valley of the Grand River and its tributaries, the European settlers who arrived in the 19th century saw the wilderness as an impediment to what they considered “progress.” Generally speaking, forests had economic value only because of the trees that could be harvested for the lumber market, but otherwise were cut down to make room for farms and towns.

Wetlands had no monetary value at all. Who would want to buy a swamp or a marsh?

Subsequently, they were drained, filled in and even had the organic layers that had once been their bottoms burned away, starting underground fires could smolder for months, leaking smoke into the atmosphere.

The destruction of forests and wetlands had a profound effect on the Grand River Valley’s environment. The natural habitat of many species of wildlife was devastated. Prime farmland suffered from erosion by wind and water.

Some of the most dramatic effects could be seen in the Grand River itself. With no wetlands to hold and naturally filter water, runoff from rain and spring melts went straight into the river. This flow was increased by channels that had been dug to carry the runoff from farms. Pollution in the form of fertilizer and manure went straight into the river, to be joined by the garbage, industrial waste and human sewage from the towns.

Wildlife in the Grand and its tributaries declined as severely as that of the lands around them.

The river was unpredictable and at times dangerous. Heavy rains, spring melt and ice-jams caused massive flooding which threatened the lives of humans and livestock, and inflicted widespread property damage. The river that had been a raging torrent in spring could be a comparative trickle in the

dry spells of summer. But though it was greatly reduced in volume of water, the river was a stinking, disease-ridden sewer.

By the turn of the 20th century it was clear to conservationists that poor land and drainage management was the cause of the river’s ailments and the problems that went with them, but nobody wanted to spend money to do anything about it.

Then in 1930, Hugh Templin took up the cause. Born in Fergus in 1896, he was the son of John C. and Annie [nee Black] Templin. John Templin bought the Fergus News-Record in 1902, and young Hugh went to work there as a student. At the age of 28 Hugh became editor. Hugh Templin had developed a profound interest in the Grand River, and letters to the editor sent in to the News-Record showed that he was not alone in his concerns about the waterway’s problems and dramatic deterioration.

He went out to personally inspect dried-up marshlands that at one time could only be crossed by boat. He knew that he was not personally qualified to make an

accurate scientific assessment of the terrain, so he recommended that a study of at least a year be made by “some competent person.” Templin believed that former wetlands that were privately owned should be purchased by the government and that a large section of the region be turned into a conservation area.

With the support of like-minded people, Templin encouraged the municipalities along the river to cooperate instead of squabbling or ignoring the problem altogether. However, that took time because some communities were not as badly affected by flooding as others, and with the onset of the Great Depression, the problem of funding loomed even larger. But in time, the voices of Templin and his allies prevailed.

In 1934 the Grand River Conservation Commission was formed. In 1938, H.G. Acres & Co. of Niagara Falls was hired to develop a reservoir plan and supervise the construction of a new dam. The cost, estimated to be about $2 million, would be shared by the federal and provincial governments and the municipalities of Fergus, Elora, Brantford, Paris, Kitchener, Waterloo, Galt and Preston [the latter two now part of the city of Cambridge].

Each municipality had a representative on the commission. Udney Richardson was there for Elora and Hugh Templin for Fergus. The project was expected to provide up to 700 jobs and take six to eight months to complete.

On July 11, 1939, at a site 4.8 kilometers east of Fergus, a crowd of about 2,000 people gathered to watch Ontario provincial government Minister of Public Works Colin Campbell use a gold-plated spade to break the earth in a ceremonial launching of the construction project.

When Canada entered the Second World War the following September, the federal and provincial governments decided the work had progressed too far and was too important to be postponed until the war was over.

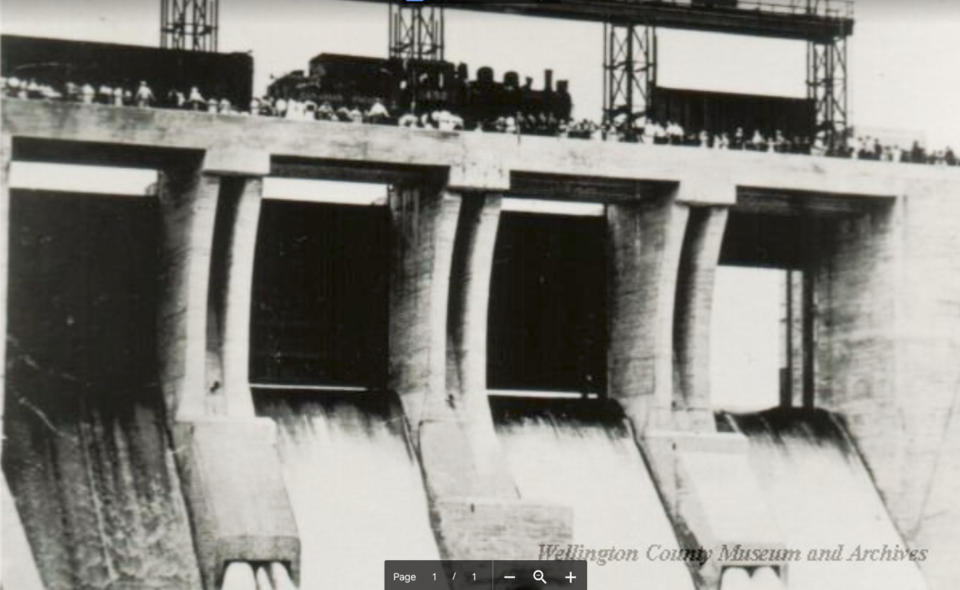

Beginning in the spring of 1940, there was a major push to complete the dam quickly. Workers broke Canadian records in putting into place and compacting 256,000 cubic metres of clay. Steel gates had to be installed, and a railway moved so that the tracks crossed the river on the dam.

The dam was officially opened on August 2, 1942. The water it held back created Belwood Lake, which soon became a popular recreation centre. Initially, the new structure was called the Grand Valley Dam, but tourists looking for it were going to the town of Grand Valley by mistake. The dam was therefore renamed after a local pioneer family named Shand.

The Shand Dam was the first large-scale, multi-purpose structure of its kind in Canada. Its construction was an engineering milestone for Southwestern Ontario. In recognition of Hugh Templin’s contribution, Ontario Premier Leslie Frost named him “The Father of Conservation in Ontario.”