This article, written by Elisabeth Rondinelli, Acadia University; Rachel K. Brickner, Acadia University, and Rebecca Casey, Acadia University, originally appeared on The Conversation and has been republished here with permission:

When the third wave of COVID-19 hit Canada and the benefits of the short-lived hero pay had long passed, workers’ advocates made renewed calls for a paid sick leave policy.

In Ontario, where the third wave was particularly devastating for working-class and racialized people, advocates pointed out that while many workers from these communities were disproportionately deemed “essential,” they were also the least likely to be able to access paid sick leave benefits.

Media coverage of the pandemic has focused public attention on these and other important workplace issues, such as the opportunities and challenges of remote work, the impact of the pandemic on women’s employment and the health and safety of essential workers.

As we hopefully near the end of the pandemic and collectively consider how to transform the workplace in ways that are safer, more equitable and humane, it’s important that the voices and experiences of essential workers are heard.

While media coverage has been crucial in fuelling public discussions about the workplace, our research shows that there’s a disconnect between the way media covered work issues during the pandemic and the stories workers felt were important for the public to understand.

Survey of workers

During the first wave of the pandemic, our research team conducted a survey of three groups of essential workers in Nova Scotia — long-term care workers, retail workers and teachers.

Our survey focused primarily on how working conditions had an impact on their health and well-being, but because essential workers were receiving more media attention, we also asked participants to reflect on how the media covered their occupations.

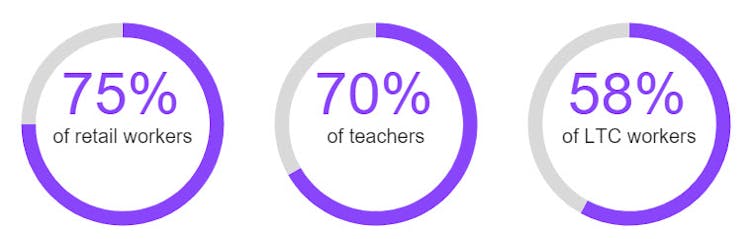

We asked survey participants if the media focused on the most important issues of their work, and 69 per cent of participants responded “no” versus 31 per cent who said “yes.” Broken down by group, retail workers were the most likely to say that the media was not covering the most important issues (75 per cent) followed by teachers (70 per cent) and long-term care workers (58 per cent).

When asked to describe how they felt about media coverage of their work, some participants expressed gratitude. One long-term care worker told us:

“I think some of the coverage has been good and it has brought to light the ‘gaps’ in the system and how some of the most vulnerable people in society are treated and prioritized.”

However, about half of the open-ended responses stated that coverage was incomplete, one-sided or that the tone became more critical over time. For example, some long-term care workers felt that coverage focused disproportionately on residents, ignoring workers:

“They have focused on the impact to residents but have not talked about the tremendous work the staff did in LTC facilities in NS to keep everyone safe. The staff were viewed as the carriers [of COVID-19] and would be blamed publicly if an outbreak occurred.”

Retail workers, teachers

Retail workers noted that media coverage was largely silent on what some saw as unnecessary risks to their health. According to one participant:

“They show us as these lifesavers and glamourize us when in reality, we’re risking our health and safety so Karen can buy Doritos and ice cream at 10 p.m.”

Teachers noted that they were often portrayed as complaining, whining or lazy, especially when they expressed concerns about working conditions. As one teacher commented:

“It has been interesting to see praises sung as the extent of our jobs was discussed, and then to be referred to in a negative light as we look for clarification of safety measures for returning to school.”

Our participants’ frustrations with media coverage of their work during the first wave of the pandemic underscore the importance of intentionally including workers’ experiences in public dialogue about the economy and public policy.

After all, workers’ lived experiences are not interchangeable with broader questions about business and the labour market, nor can we understand workers’ experiences through a near exclusive focus on policy. Ignoring workers’ experiences leads to missed opportunities for understanding how policy and working conditions can improve.

Blaming the benefits

As a case in point, some Republican governors in the United States recently attributed labour shortages in the food services and hospitality sector to overly generous COVID-19 unemployment benefits provided by the American Rescue Plan.

While economists rejected that connection, worker-centred media coverage provided important insight into why workers were turning away from food services.

In post-pandemic Canada, media will also play a crucial role in shaping public understanding of labour conditions. If we’re committed to creating a future of work that is safe and equitable, workers themselves must be a central voice in the stories that media tell.![]()

Elisabeth Rondinelli, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Acadia University; Rachel K. Brickner, Professor of Politics, Acadia University, and Rebecca Casey, Assistant Professor, Sociology, Acadia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.