Most communities look back through history to one person as a founder.

Guelph, for example, was founded by John Galt. Toronto credits John Graves Simcoe.

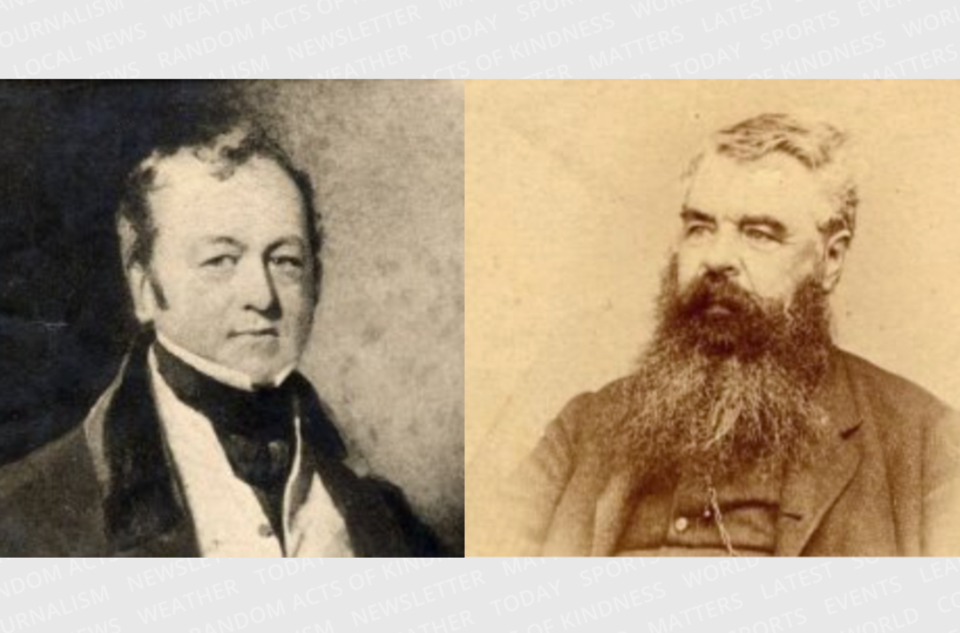

Fergus has the distinction of having two founders; Adam Fergusson and James Webster. Both were born in Scotland to affluent upper-class families; Fergusson in 1783, and Webster in 1808. Both were well-educated and had trained to be lawyers, but forsook the legal profession to seek their fortunes in the wilds of North America.

In Scotland, Fergusson was a magistrate and a deputy lieutenant of Perthshire. He was also a director of an agricultural association called the Highland Society of Scotland which encouraged improved farming methods and emigration to North America.

In 1831 the society sent him to investigate Canada and the United States as destinations for Scottish tenant farmers displaced by the notorious “clearances.” Fergusson was impressed with what he saw in what was then called Upper Canada, and wrote about it in the Highland Society’s journal.

His wife Jemima (nee Johnston) had died in 1825. In 1833 Fergusson and six of his seven sons moved to Canada and settled near Waterdown. He built a home there he named Woodhill after his family’s estate in Scotland.

Webster came to Canada with Fergusson’s party. Unlike Fergusson, he was not an eldest son and so was not heir to the family estate. However, he did inherit money which he invested with Fergusson in the founding of a new community, Fergus, on property formerly called Little Falls which they purchased in Nichol Township.

They had decided the soil there was “first rate” for farming.

To Webster, the business of carving out a settlement in the wild country was not just a financial enterprise, it was an adventure. Fergusson could be called the senior partner in that he was the larger landholder, but Webster was the one who lived on the site and worked side by side with the first Fergus pioneers.

With the help of earlier settlers from Elora and other nearby fledgling communities, he built a log cabin where he and a man named William Buist spent their first Canadian winter. They had to walk to Guelph for supplies.

Fergusson said he would build a church “as soon as a Church of Scotland clergyman could be obtained.”

They built a second structure, a six-room cabin they called “the Cleikum” after the legendary Scottish shepherd’s crook St. Ronan used to subdue the devil. New settlers stayed there until they could build homes of their own. Many of the streets in Fergus were named after those original homesteading families.

Webster’s first actual house was at the site of Kinnettles. Later he constructed his grand Mansion House on Gowrie Street. It became a centre for Fergus social life.

Webster and his wife Margaret (nee Wilson) were known for the grand balls they held every year.

Webster built several stores, a distillery, a grist mill and a sawmill, with the fast-flowing Grand River providing the water power. When the grist mill burned down, with the loss of much of the local farmers’ harvest, Webster compensated them out of his own pocket. Then he personally invested in the construction of a new mill.

Webster served as a commissioner for Nichol Township and as district councillor. He was also the councillor for the Court of Requests. He also enlisted in the local militia, rising to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. Webster represented West Halton and then Waterloo in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada from 1844 to 1848.

Later he moved to Guelph and became the town’s fourth mayor. He represented North Wellington in the legislative assembly from 1857 to 1859, and then was appointed registrar for Wellington County.

Fergusson, described by Sir George Arthur, the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, as “a gentleman from Scotland, highly respectable and intelligent,” was somewhat more the country squire in his bearing than Webster.

He and Webster clashed over the question of who should be allowed to settle in Fergus. Webster was a magnanimous person who believed anybody willing to do the work of establishing a homestead should be allowed to buy land. Fergusson did not want land sold to anyone he considered undesirable. That included the Irish.

In 1838, Webster went to Scotland to visit relatives, and Fergusson and his family moved to Fergus to look after the settlement in his absence. Soon a petition was being circulated around town to have the community’s name changed from Fergus to Websterville. When Webster was presented with the petition, he declined the honour and said that Fergus was named after Fergus Mor (Fergus the Great), a legendary fifth century Scottish king.

That ended the petition, but not the rift in the relationship between Fergusson and Webster.

Fergusson was staunchly loyal to Britain, and served as a militia commander during the Mackenzie Rebellion. However, although he had much in common with the hard-line Conservatives of the Family Compact who dominated Upper Canada’s politics, Fergusson supported the more liberal-minded Reformers. He was appointed to the Legislative Council for Upper Canada in 1839, and then became a member of the Legislative Council for United Canada.

Fergusson had a lifelong interest in developing and promoting good agricultural practices and in improving livestock breeding. He was one of the first to import pure-bred, short-horned cattle from Britain. He was the first president of the Agricultural Association of Canada, and was instrumental in bringing Dr. Andrew Smith from Scotland to found a veterinary school in Guelph – now part of the University of Guelph.

Fergusson was actively involved with the Reform Party and was associated with George Brown and William McDougall, both of whom became Fathers of Canadian Confederation. Fergusson might very well have been included in that group of men, but he died in Waterdown in 1862, five years before Confederation, after suffering a paralytic stroke.

Like Fergusson, Webster did not die in the town he’d helped to found. He passed away in Guelph in 1869.